I was diagnosed with TB infection after undergoing an occupational health screening required for my nursing school clinical placements. Receiving a TB diagnosis was frightening, since, like many people, I wasn’t aware that TB was still a concern. I was upset and scared about what this meant for my health and my future.

However, my care providers were empathetic, compassionate, patient, and highly knowledgeable about the disease. They took the time to thoroughly educate me and offered a range of follow-up options. After careful consideration, I chose to treat my latent TB infection to reduce the risk of developing active TB in the future.

However, my care providers were empathetic, compassionate, patient, and highly knowledgeable about the disease. They took the time to thoroughly educate me and offered a range of follow-up options. After careful consideration, I chose to treat my latent TB infection to reduce the risk of developing active TB in the future.

I worked as a summer student delivering the Directly Observed Therapy (DOT) program, where trained healthcare providers administered treatment and supported patients and families throughout their care, offering a direct link to those affected by TB. I started working at this clinic at the same time I was receiving treatment for latent TB. At that time, treatment involved taking 78 doses, twice a week, for about nine months. Through this experience, I gained first-hand insight into how disruptive, exhausting, and frustrating it can be to coordinate a nine-month treatment regimen while trying to maintain a normal life.

Addressing Misunderstandings About TB

TB is still widely misunderstood, both in terms of its impact on affected populations and the disease itself. With 14 years of experience in public health focused on TB care across different regions of Canada, I’ve found that we face similar challenges in our efforts to eliminate TB. One of the most critical steps in addressing these challenges is tackling the stigma surrounding TB, and those affected by it. A key action would be to prioritize community-level education and awareness about TB. Additionally, the Canadian government has committed to reconciliation, with specific calls to action for health, which must include addressing TB in Indigenous communities. As an Indigenous nurse providing care to these communities, I advocate for all healthcare providers to develop a deeper understanding of TB. I believe that by fostering open dialogue about the disease and working collaboratively, we can create tailored, culturally appropriate plans to meet the unique needs of each community based on their culture and location.

Barriers to TB Prevention

The historical treatment of Indigenous peoples in Canada, particularly in relation to TB, has contributed significantly to stigma and mistrust surrounding the disease. Indigenous peoples were often subjected to discriminatory practices in TB sanatoriums, where they faced segregation, mistreatment, and a lack of cultural sensitivity. This legacy of trauma has led to a deep mistrust of healthcare systems, which continues to affect their willingness to seek care for TB today.

The stigma surrounding TB, compounded by historical injustices, discourages individuals from getting tested or seeking treatment, fearing discrimination or negative judgment. This mistrust also hinders effective communication and education about TB prevention and treatment, creating barriers to care. As a result, efforts to eliminate TB in Indigenous communities are undermined, as the disease remains underreported and undiagnosed due to fear and stigma.

TB Prevention and Treatment in Saskatchewan and Beyond

As an Indigenous healthcare provider in Canada, there is much to be hopeful about when it comes to advancements in TB care and treatment, especially considering the disproportionate impact TB has had on Indigenous communities. Historically, TB has had devastating effects on Indigenous populations, rooted in colonialism, social determinants of health, and limited access to healthcare. However, recent progress is making a difference in both the treatment and prevention of TB in Indigenous communities, and this offers hope for a healthier future.

Some things I look forward to for TB prevention and treatment include — but are not limited to — improved diagnostics and access to testing, tailored treatment regimens and shorter treatment durations, culturally relevant and community-based approaches, better public health infrastructure and collaboration, and strengthening the role of Indigenous healthcare providers.

Breaking the Stigma: TB Education and Awareness

- Correcting Misunderstandings: By providing accurate information about how TB is transmitted, treated, and prevented, education can dispel common myths and misconceptions, such as the idea that TB is always fatal or highly contagious through casual contact. This helps reduce fear and misinformation that often fuel stigma.

- Highlighting TB as a Treatable Disease: Educating the public about the effectiveness of modern TB treatment and the fact that people with latent TB are not contagious can help shift the narrative from one of shame and fear to one of hope and recovery. Including the knowledge that TB can be treated in your community, and most often in the comfort of your own home may encourage engagement.

- Addressing Historical Trauma: Education about the historical mistreatment of Indigenous peoples and their experiences with TB care in past decades can foster understanding and empathy, while acknowledging the roots of mistrust in healthcare systems.

- Promoting Cultural Competency: Awareness training for healthcare providers can lead to more culturally sensitive care, reducing instances of discrimination or misunderstanding that may arise when Indigenous peoples seek TB treatment. This can help rebuild trust in health services.

Overall, education can shift attitudes from fear and shame to understanding and support, which is essential for both reducing stigma and improving TB elimination efforts.

Outlook for the Future

While there is still much work to be done, these advancements in TB care—ranging from new diagnostic tools and treatments to culturally tailored care and stronger community-based interventions—offer hope for a future where TB is no longer a significant health burden for communities in Canada. The active involvement of Indigenous healthcare providers and the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives in healthcare planning and research are key to making these advancements sustainable and truly effective for those who need it most.

Thank you for supporting lung health in Saskatchewan.

Yours sincerely,

Tina Campbell

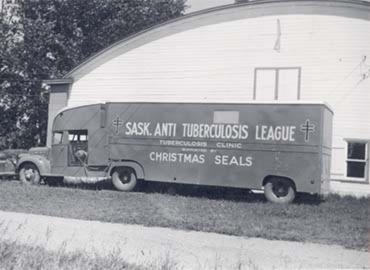

For 113 years, Lung Saskatchewan has been dedicated to improving lung health, with its roots in tuberculosis (TB) care tracing back to the days of Saskatchewan Sanatoria located in Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatoon, and Prince Albert. To fight this highly contagious disease, the Saskatchewan Anti-Tuberculosis League was established in 1911.

Under its auspices, the Fort Qu’Appelle Sanatorium was established in 1917, offering rest and fresh air as treatment. However, the cure was long and tedious, and many could not afford to stay until they were fully healed. In 1929, thanks to the League’s efforts, Saskatchewan became the first province to provide tuberculosis care and treatment free of charge.

Under its auspices, the Fort Qu’Appelle Sanatorium was established in 1917, offering rest and fresh air as treatment. However, the cure was long and tedious, and many could not afford to stay until they were fully healed. In 1929, thanks to the League’s efforts, Saskatchewan became the first province to provide tuberculosis care and treatment free of charge.

Our mission continues to grow and adapt to the changing needs of communities across the province. While we have transitioned the care of TB patients to the Saskatchewan government, we remain committed to supporting them. Lung Saskatchewan provides resources and education to help TB patients on their journey to better health. Leaders like Tina Campbell also continue to play a vital role in this work, especially in supporting tuberculosis prevention and care in northern and First Nations communities.

Tina is a Registered Nurse, a board member of Lung Saskatchewan, and the TB Advisor for the Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority (NITHA) in Prince Albert. NITHA supports 33 First Nations communities with a combined population of over 55,000. Tina also serves as the co-chair of Stop TB Canada, a network dedicated to ending tuberculosis both at home and abroad.

An Indigenous woman of Cree ancestry, Tina lived the majority of her life in Nunavut, where she also began her career working with patients affected by TB. Tina’s dedication to TB awareness garnered international recognition when she was invited to the United Nations in New York in May 2023. As co-chair of Stop TB Canada, Tina spoke as a panelist at the Multi-Stakeholder Hearing on the ‘Fight Against Tuberculosis’. She represented civil society and affected communities in Canada, and called for urgent action in the fight to end tuberculosis.

Did you know many people believe that TB is no longer a significant health threat, assuming it was eradicated or is only found in history books? In reality, TB is still a major global health issue, with millions of new cases each year.

Learn more: Common misconceptions about TB.